Welcome to EastKeep! Thank you for reading. You can find out more about this newsletter and me here. I intend to write about things that span the space of my somewhat interesting professional experiences and my maybe-boring-maybe-not personal undertakings.

People spout a lot about allyship, but is it what needs to be said? Is it enough? What, really, makes an ally effective? I don’t want to burden any POC with these questions. They are questions I must answer for myself, and ask of my White friends and family.

In my two decades teaching and living on the Flathead Indian Reservation, I spent a lot of energy trying to convince people I was an ally, without using that word. I said things like “I try to meet the students of the community I serve where they are, instead of insisting they meet my standards.” And, “I am a guest here.” These things are true and I meant them, but how self-aware was I, really?

The book Research and Reconciliation: Unsettling Ways of Knowing Through Indigenous Relationships contains a chapter written by one of its editors, in which she spends several pages painfully and self-consciously investigating her own Whiteness/awareness. It’s quite striking, particularly when she reaches this quoted material:

Settler moves to innocence are those strategies or positionings that attempt to relieve the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land or power or privilege, without having to change much at all. In fact, settler scholars may gain professional kudos or a boost in their reputations for being so sensitive or self-aware. Yet settler moves to innocence are hollow, they only serve the settler.

Ouch, that might be me.

The author of that chapter in Research and Reconciliation also discusses why a White person doesn’t even have a say in this conversation. And while I agree with that in some ways, such as - I shouldn’t be taking up space where a POC should be working - sometimes White allies must have a say, because who else is going to say anything when no Indigenous people are present?

This happened.

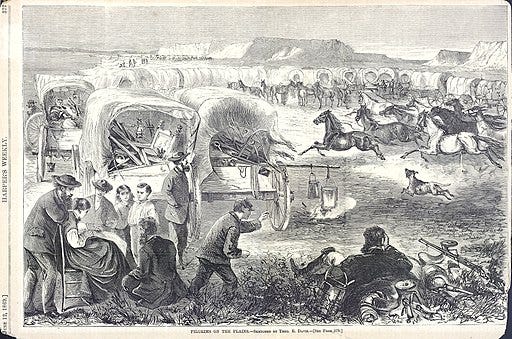

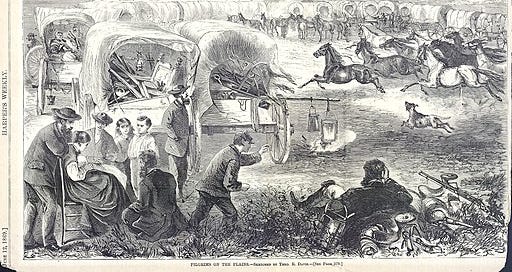

So I was in this online class about Indigenous literature “and the West” for a while. I should have known “and the West” was going to be a problem. We were asked to read a 5000-word Frederick Turner essay from 1893 glorifying colonizers’ ongoing struggle with the frontier as what created American character: gritty, persistent, holy.

I had some things to say in a discussion forum about his erasure of Native people, and I was instantly taken to task by several of my classmates for criticizing someone who was “simply a product of his times.” One of them even complained to another student in a post that was visible to all, about how tired she is of people criticizing historical artifacts using “today’s terms.”

I immediately wanted to drop the class, I was so disgusted with the attitude (and with the course reading list). A friend told me that nobody would blame me for dropping the class, but also said, “this is your chance to be an ‘ally’ if you choose to.” I thought about this. What good am I if I don’t use my ability to illuminate people’s ignorance for them at the time when it occurs? So I dropped the hammer on those classmates. As part of a lengthy response, I wrote,

Yes, certainly Frederick Turner was a product of his time. So was Robert E. Lee, and so was Andrew Jackson, and so was John James Audubon, who was a slaveowner. As Black ornithologist J. Drew Lanham points out in this essay discussing Audubon’s racism, “Racists do not get passes because of identity confusion or historical context. None.”

…Reading this Turner essay and excusing his “perspective” by way of allowing that he was a product of his time, in my opinion, is the same as arguing to keep Confederate monuments in place, and has the same effect: in critiquing these statues, we maintain their relevance, and thus honor them. The only ethical way to deal with them is to confront, and remove them from the conversation.

I dropped the hammer. And then I dropped the class.

Bewilderment ensued.

I was stunned. In a Native American Studies course, housed in a NAS department at a major university…sure, academic freedom is a thing. But haven’t we “academics” passed the point of defending racists who are “a product of their time”? It baffles me how these classmates were able to blather on in their posts about how interesting Turner’s essay was to them, and then insist that I was the one missing the point.

I have a personal-life rule that I more or less live by: if a group of unrelated people say the same thing about another person or thing, they’re probably in the right. Think about that friend who “always has shitty roommates” or that boyfriend who complains about his many awful bosses who always tell him to fix his attitude. Bruh…it’s not them. It’s you. Think about what you’re doing.

Bruh…it’s not them. It’s you.

So was this me? Was I actually the one missing the point? I thought a lot about this. I talked to others. And finally I concluded that for once no, I was not the one missing the point, and here’s why. Because first of all, that Frederick Turner attitude of elevating the settlers above everyone else and erasing the Indians in his narrative, that racism still exists, at least here in Montana. There are movements afoot in our current legislature to abolish reservations, for example. There is constant pushback against Indian Education for All in schools, sometimes by educators themselves as well as community members. Our tribal communities are always having to fight voter suppression efforts.

Entertaining Turner’s concept of the frontier is offensive in light of the way tribal communities have had to fight for every inch of the land they do have, their sovereignty, language, and culture. Especially in a NAS class! Moreover, keeping those narratives alive without interrogating them, to use a fusty academic word, allows them to stay relevant. It communicates, “Let’s keep talking about this idea.” No, let’s not.

What is my role?

Back to allyship. I waffle between feeling like I need to educate my fellow White people, and saying fuck it, I should really just worry about myself. Because who among us doesn’t need some personal work? Also I don’t like feeling like I’m “that guy” - the one with a bunch of answers, the holier-than-thou attitude, the self-righteousness. And I especially don’t want to come off as that guy in situations where I’m interacting with Indigenous people. Because truly, I know nothing.

At the same time, how do I carry forward if opportunities exist for me to help call out some bullshit, and I don’t do it? As my friend Michelle (Salish) says, “We are always going to need advocates supporting our efforts to heal ourselves and our communities, whenever there’s opportunities.” Anishinaabe writer Chris La Tray (Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians) also told me that non-Natives have a role to play. “We are all relatives. We are all in this together, and we must work together if we are going to preserve anything at all. Languages, the world, everything.”

Here’s what it comes down to: White people need to act better. We need to be willing to say, “it’s not everyone else, it’s me. What can I do differently? What actual things am I doing that are using and perpetuating my own privilege and the system of racism to benefit myself?” If you feel pissed off or defensive reading this, then you haven’t begun to figure it out. You’re still trying to say “it’s not me…it’s all of them.”

Specific to working with Indigenous people, there are some things White people can do differently - I’ve written about some of them here. But in general, and I’m not saying anything that plenty of others haven’t already said, we reap the rewards of a system that elevates us over POC and we need to acknowledge that. Then maybe allyship can begin to happen.

"Moreover, keeping those narratives alive without interrogating them, to use a fusty academic word, allows them to stay relevant. It communicates, “Let’s keep talking about this idea.” No, let’s not."

💣

Again, wow. I’m rethinking some things (in a much different context) that I used to use to explain away the wholesale slaughter of animals “back in the day”. Sadly, my teaching days, at least as far as where and who I used to teach, are probably far behind me.