So I wrote this paper last year for a great class I took with Dr. Jeff Sanders at MSU. I’m off-grid for the coming week and haven’t written anything for a while because I was teaching 3 online classes and … life … but felt like this might be a good time to share parts of the essay. It’s not the whole thing, K? Because nobody needs that much academic language. But I liked writing this paper and if you’re interested in Indigenous education and/or doing education stuff differently, you might find something useful in it.

Introduction

In the efforts to revitalize Indigenous languages, course designers are generally working within a Eurocentric framework that coordinates with a traditional American public education approach. This is an inappropriate way to design courses that should be aligned with Indigenous values, epistemology, and pedagogy. Courses teaching about Indigenous languages and culture should themselves be Indigenized. But what does it mean to Indigenize a course, and how can Indigenous theories of education be incorporated meaningfully, particularly by a non-Indigenous course designer?

According to the United Nations, an Indigenous language is lost every two weeks. UNESCO has designated this as the decade of Indigenous languages to draw attention to this crisis and to promote revitalization. Successful revitalization efforts are crucial because language is the underpinning of culture. Without language, there are no ceremonies. Entire cultures vanish if the people within them can no longer express their identity in the same ways they have done for millennia.

This most devastating loss is a direct result of colonization, primarily by European settlers over the last few centuries. With every required English class, every tax code, every Eurocentric approach to our society, from education to governance, colonization is perpetuated, and languages continue to disappear.

Language revitalization efforts have been ongoing worldwide now, in some cases for decades, and in other cases for just a few years. Hawaii presents one of the most successful cases. Hawaiian language had nearly vanished by 1970 but has since been re-energized through a handful of coordinated and sustained innovative efforts. One of the features of this successful effort has been the steps taken to Indigenize the instruction. At a 2022 Great Falls, Montana, language conference, Dr. Kū Kahakalau made a strong argument for embedding traditional practices into language instruction. Examples include singing the morning song before each day’s work began and creating community through collaborative activities throughout the day. These practices reflect the culture attached to the language being taught, and speak to Indigenous students on a level that Western education alone cannot.

One of Montana’s creative approaches to address language revitalization has been to harness the Montana Digital Academy to provide online instruction in Indigenous languages to high school students. Funding was not provided to hire someone to do this work, so the person already on staff most closely qualified to create these courses was selected. That person is me: White, and despite long-term ties to a reservation, I do not possess first-hand cultural or language knowledge of any tribe whatsoever. Thus, the courses I aim to create will reflect my experience, which is extensive but thoroughly Western. That is, I know how to design courses that are linear, cumulative, siloed, centered on the individual student, and thoroughly divorced from spirituality. These courses are also assessed traditionally - that is to say, with somewhat arbitrary percentages translated to even more arbitrary letters and attached to seat time which aligns with Carnegie units.

However, I find that Dr. Kahakalau is only one voice of many, insisting that for Indigenous students, particularly those involved in Indigenous or cultural studies of any kind – including language – the instruction itself must be Indigenized. It must be decolonized. As the person building these courses, it is my responsibility to embrace and engage this pedagogy. Yet as a White person whose interaction has been limited strictly to outsider/observer, it is also a real challenge. I am not sure what to do. Thus this paper addresses the question, what does it mean to Indigenize a course, and how can Indigenous theories of education be incorporated meaningfully, particularly by a non-Indigenous course designer?

Theoretical Overview

First, a distinction between “decolonize” and “Indigenize” may be helpful. To “decolonize” pedagogy, according to some thinkers, is to “decouple” Western approaches from Indigenous education to prevent Western education from contaminating it. In the context of this paper, I am specifically seeking to learn how to more closely align my courses with Indigenous epistemologies and values. Yet I cannot discard some of the Western frameworks embedded in the courses I build. For example, they are constructed in a learning management system that is linear (scrolls from top to bottom). We are required to report course percentages to schools for the purpose of assigning grades. The Carnegie unit is inescapable. We can be creative with some of these requirements and restrictions, but it’s more a question of how to circumvent them, not blow them up. Decolonizing the courses may not be a reasonable hope.

However, to Indigenize the courses may be feasible. According to Wildcat, to Indigenize “is the act of making something of a place.” Another thinker asserts that this type of work must be done in partnership with the oppressed, not for them in a paternalistic fashion. Thus, in collaboration with Indigenous language communities, a new pedagogy can be forged, one that honors and centers Indigenous ways of knowing.

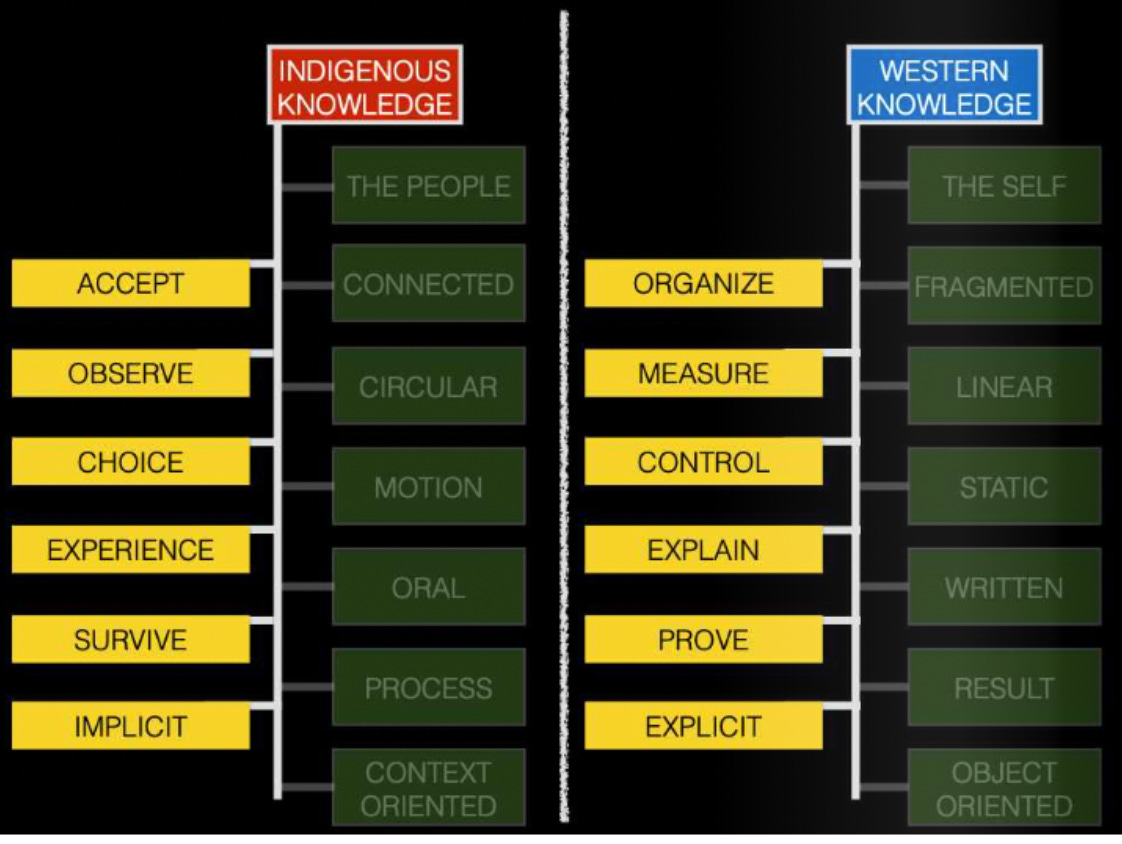

In her language, culture, and pedagogy course “Who We Are: The Nakona,” Dr. Crystal Redgrave cites Vine Deloria in a chart, which is a helpful initial step toward considering some of the pedagogical differences between Western and Indigenous education.

Whereas Western education focuses on the individual, fragments knowledge into discrete segments, and seeks to rationalize understandings, Indigenous epistemology contextualizes information in terms of observation, community, and interconnectedness. This helps explain some of Dr. Kahakalua’s insistence on integrating traditional activities into lessons, as those activities underscore and strengthen community.

Consider the way typical Western education systems separate subjects from each other, segments of the day from each other, and even student age groups from each other. Referring to the chart above and Dr. Kahakalua’s suggestions, we can begin to perceive what it might mean to Indigenize education: remove arbitrary barriers, erase the Carnegie unit, facilitate community rather than individualism, and teach subjects in an integrated, discursive, and experiential way.

Review of the Literature

I’m not pasting this section. It’s a lot. There’s a summary below. But some thinkers I cite here include Cajete, Deloria, Wildcat, Pewewardy (all dudes. Why? Where are the women?) I’ll add a footnote1 with their info.

Findings

Back to the paper…

The themes which emerge from this literature selection are unified, if not monolithic. First, the writers are unapologetically committed to an Indigenous-originated pedagogy. No education of Indigenous children should occur without the complete and exclusive input of tribal thinkers, particularly elders. No education about Indigenous topics should take place without guidance from tribal thinkers.

Second, these texts highlight the importance of context. That is, community and the natural world as they overlap with students’ experiences must play a key role in the education of these students. As Deloria noted, most students live away from such contexts, and these must be re-created for them in the form of stories, cultural information, and authentic teachings from elders where possible. People are not separate from their contexts, and to resist the impulse of Western thought to separate and analyze things in terms of their parts and functions is to take a step toward Indigenous thought and education.

Third, respect for this natural world, the land, and other humans is a critical element of Indigenous approaches to the world, including education. This is part of what it means to understand one’s context; yet, to develop into the kind of human who can live harmoniously within that context is the purpose of education, according to many of these thinkers.

Much of this guidance can, in fact, be integrated into online course design for Indigenous languages. There are ways to build positive community in online environments which involve discussions, check-ins, student interaction, and teacher feedback. Furthermore, a respect and understanding of land and the natural world may seem unrealistic for an online class, yet bringing these components of “real world” virtually into a multimedia course is feasible through video, audio, and other functions within the online course platform. Finally, to return to the initial theme, guidance by the tribal community is key to ensuring cultural alignment, appropriateness, and adequate information in order to best meet the needs of the students served. Building these partnerships should in truth be the very first step any educator takes in considering a course involving any Indigenous content or students.

Conclusion

In my attempts to understand what “Indigenous education” might mean and how to apply it to my work, I have focused on the parts of these texts that seem applicable to my situation. Yet at least two confounding components persist. One is that the students who will take the classes I develop are not all Indigenous students. This isn’t truly a problem, as I believe the underpinnings of an Indigenized educational experience will benefit any and all students who experience it. For example, in what way could “respect for the natural world and other humans” be detrimental to anyone? It’s simply a misalignment between the question I asked and the potential solutions I found.

The larger problem is this: As an outsider how do I participate in this activity of Indigenizing the courses I am required to design, except in a superficial and deferential way? It is a question for another research project.

I continue to struggle with the concepts, though this struggle has brought me closer to an understanding of what it is I’m trying to do. The research involved in this paper has helped me have meaningful conversations with others about the purpose and intended outcomes of the classes, solidified and challenged some of my ideas about the course design, and given me plenty of food for thought regarding future courses. For that I am grateful.

Cajete, G. (2012). Decolonizing Indigenous education in a twenty-first century world. In Yellow Bird, M. & Waziyatawin (Eds.), For Indigenous minds only: A decolonization handbook. School for Advanced Research Press.

Deloria, V. & Wildcat, D. (2001). Power and place: Indian education in America. Fulcrum Publishing.

Garcia, J., Shirley, V., & Kulago, H.A., Eds. (2022). Indigenizing education: Transformational research, theories, and praxis. Information Age Publishing.

Pewewardy, C., Lees, A.. & Zape-tah-hol-ah Minthorn, R. (Eds.) (2022). Unsettling settler-colonial education: The transformational Indigenous praxis model. Teachers College Press.

This is also something that has been weighing heavy on my mind lately, and I agree with you on so many points - especially as I am supporting indigenous educators and communities in a few different ways right now. It is least likely that K-12 school systems in the U.S. can be decolonized (per the definition, which I appreciate you adeptly sharing). However, communities and allies such as ourselves can help support indigenizing education systems. Even for non-Indian/Native peoples, all of those attributes you listed - community, context, and interconnectedness - are good for every soul in their understanding and learning about themselves and the world around them. I feel like we are at a ripe moment in K-12 educational innovation. The trend in cultivating learners at the "whole-person" - and in a growing number of cases, "whole community" level - continues to gain momentum. Intentionality will help fuel this movement... I'd be up for deeper discussion over coffee or something soon, if you'd like =)

There are many things I could say about this piece that I won't write here. (Maybe over a drink some time?) The one thing I will say is that of all the non-native people they could have picked, they choose the right one. Your knowledge, experience, humility, and willingness to seek help from tribal elders to do what's best for our young native learners is inspiring.

Thanks for doing what you do.